|

Tears for a Clown

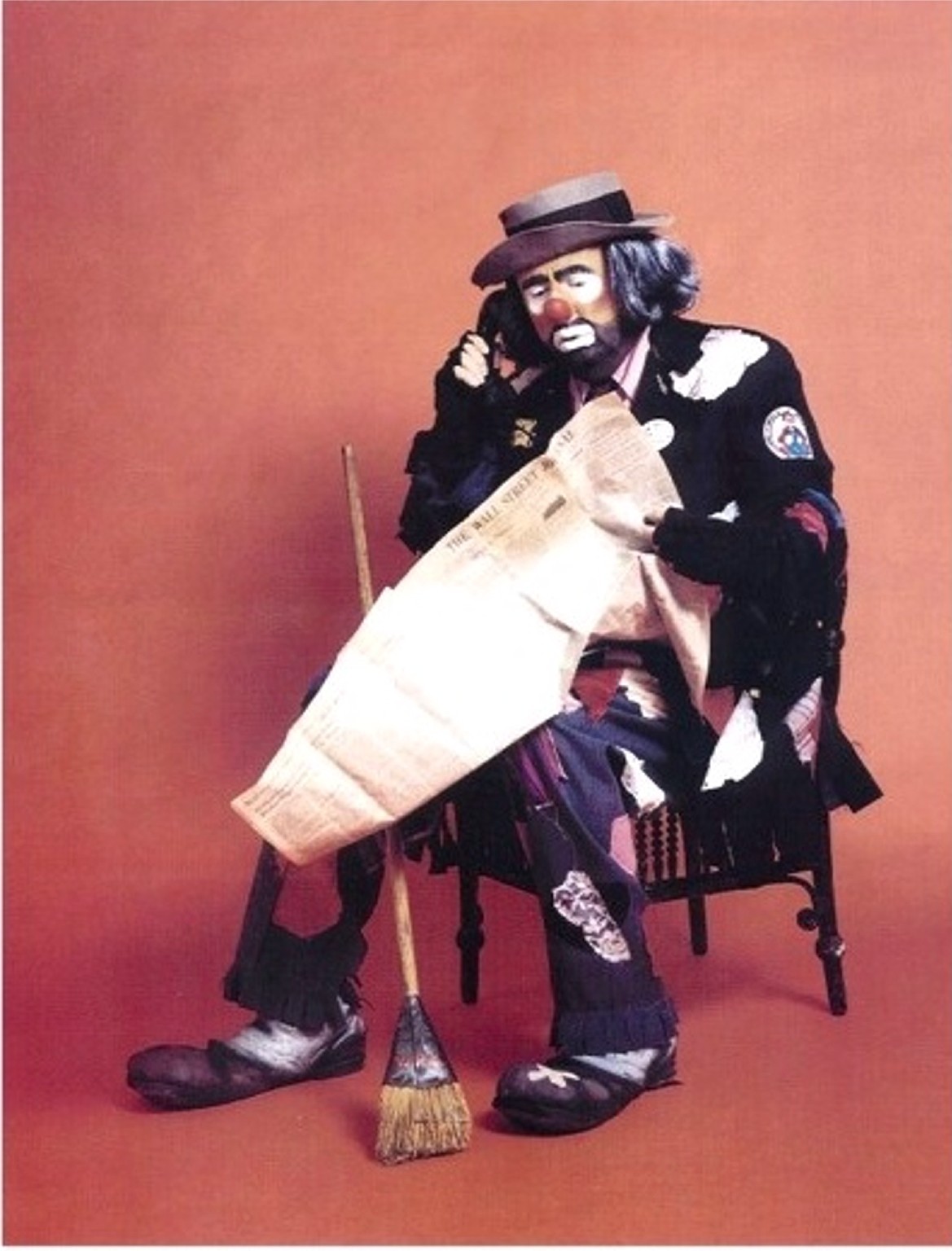

Hundreds of clowns promise to carry on the unlikely ministry of Don 'Ski' Berkoski

who taught thousands to heal with laughter.

By John J. Shaughnessy

Indianapolis Star

February 4, 2001

VALPARAISO, Ind.

They have vowed to continue their teacher's inspiring

work, so many of them have come dressed in clown costumes, with orange and

yellow wigs -- not your usual sign of respect at a funeral.

Then again, it's not exactly typical for the flowers at a funeral home to be

made of red, blue, yellow, orange and purple balloons twisted together.

Or, for the person in the coffin to be wearing a round red foam nose.

Or, to have one of the deceased's favorite sight gags -- a sign that reads,

"NOTICE! Do Not Pay Attention To This Sign!" -- attached to his casket.

Or, for a documentary film crew from Los Angeles to be here in this far

northern Indiana community, capturing this moment.

But the life of Don Berkoski wasn't exactly usual either. For 20 years

before his death Jan. 19 at age 62, the longtime Indianapolis resident had

volunteered as Ski the Clown, bringing joy and hope to places where those

emotions were too often missing. He trained 5,000 more clowns to help reach

all the lonely people in the hospitals, nursing homes and prisons that

served as his stage.

He also achieved his goal of making sure his mission would continue after he died.

"He wanted his entire training course to be on video so he could still train

clowns after he was gone," says Ruby Berkoski, his wife of 43 years and the

mother of his seven children. "He saw that dream come true before he died,

and he was really, really happy."

The virtual training already has been used successfully in Fort Wayne,

Evansville and Marion, Ruby says.

"We've already had 60 new clowns who have graduated because of the video,"

she says. "They've all signed an agreement that they'll commit to

volunteering a year in a hospital, a nursing home or a handicapped facility.

Anybody can train now with the video. His dream all these years was to take

this idea worldwide."

When he knew he was going to die soon, Berkoski dreamed of a funeral filled

with clowns and balloons, even giving his friends and family the red foam

noses to wear when his heartbreaking battle with prostate cancer

finally ended Jan 19.

"It's like a circus here," a son, Don Berkoski, says with a smile as he

looks around Dykes Funeral Home in his father's hometown. "Look at all these

clowns. There's so much happiness and joy here. That's the way he wanted it."

The clowns are the first to line up to say their final farewells Jan. 23 to

the man who taught them how to put on makeup, develop routines and connect

with an audience. Most of their faces are made up in permanent smiles, but

their tears still fall.

Others grin one more time at the red foam nose on Ski's face, a touch that's

typical of the man who also has a Smiles Unlimited Universal Clown Ministry

pin on the lapel of his blue suit.

The idea for his ministry began in 1981 at an unlikely place, the Indiana

State Prison in Michigan City, in a room that had bullet holes in its windows.

As he shared his life as a Christian with a group of prisoners, Berkoski had

a strange inspiration: He would become a clown, share his antics with the

inmates and open his heart and soul in the hope of communicating with them

on a deeper level."Crazy" idea works.

His friends and family told him he was crazy until an even stranger thing

happened: The inmates responded overwhelmingly to Ski the Clown. So did the

residents of the nursing home he visited once a week.

So Ski started his ministry, traveling around Indiana to train people in

the art of spiritual clowning, doing it all for free. And the volunteer effort

soared after Berkoski's sales job led him to Indianapolis in 1985.

"It's very important for his work to continue," says Barbara Hittle, one of

Ski's clowns who is also the coordinator of volunteer services at St.

Vincent Hospital in Indianapolis. "The clowns bring a lot of joy to people.

It's a good thing for little kids to older people. Even the staff gets a

kick out of it. It epitomizes the whole idea of what a religious ministry

should be: reaching out to people who are a lot less fortunate."

Ski's clowns promise they will continue that ministry. They know how much it

has meant to them, too.

"Before I met Ski, I didn't know I was capable of giving so much," says

Loni Ropkey, an Indianapolis woman also known as Wazzle the Clown. "He

showed me how little it takes to give to someone else. And when you give, you get

back 100-fold.

"He always told us, on the day we least wanted to clown, we would get the

biggest blessing. And it was absolutely true. You didn't have to do magic,

juggle or make balloon animals. You just had to listen and let people know

that you care. We'll continue his work."

A different view

The yellow smiley-face balloon floating above the casket is removed. The

lid is closed. Soon, the long procession of cars to St. Paul Catholic Church begins.

Nancy Gershwin is part of that procession. The producer-director from Los Angeles

has spent the past five months trying to capture the essence of Berkoski's life for

a documentary film.

She knows that Ski was diagnosed with cancer in 1997, and that, two days

later, he was on the road to train 24 new clowns.

She has heard the stories of the people whose lives he touched, including

the little girl at the Indiana School for the Blind. He encouraged the girl

to touch his floppy shoes, his frumpy hat, his tattered clothes and his big

nose -- leading her to exclaim, "Ski, I can see you!"

She has listened to his thoughts on life, including: "When I put on the

makeup, I see the world the way Christ wanted us to see it. There's no

hatred, no hurt. My whole philosophy is, 'When you look at people, you have

to see Jesus in them.' My life has been special because of that."

"It's sad," says Gershwin, whose father also died of prostate cancer.

"He's a remarkable human being. He shows how somebody can make a difference in

the world."

A wonderful life

At the church, Monsignor John Charlebois gives the eulogy. When he reaches

the point where he talks about Berkoski's efforts as a clown, the

white-haired monsignor places a red foam nose on his own face.

Later, the longtime friend reads "A Clown's Prayer," which Berkoski had

printed on his business cards:

"Lord, as I stumble through this life, help me to create more laughter than tears,

dispense more happiness than gloom, spread more cheer than despair.

Never let me become so indifferent that I will fail to see the wonder

in the eyes of a child or the twinkle in the eyes of the aged. Never let me forget

that my total effort is to cheer people, make them happy and forget at least

for a moment all the unpleasant things in their lives. And Lord, in my final

moment, may I hear You whisper:

“When you made My people smile, you made Me smile.' “

When the funeral Mass ends, Ruby Berkoski walks behind an honor guard of

clowns for her husband's casket. She is smiling, just as she has all day.

"What a life, what a wonderful life that he lived," she says. "His

favorite saying was a quote from Mother Teresa: 'Unless life is lived for others,

it is not worthwhile.'

"That's how his whole life was. He lived for others, and he had a lot of fun

doing it. It's going to be pretty lonesome without him, but I didn't want

to see him suffer anymore."

Then she walks into the sunshine with her family, her friends and the clowns

around here, all part of a day that is marked in the same way that Ski the

Clown signed his correspondence:

"Love, laughter and tears."

|